As we grapple with the pressing challenges of climate change and social inequality, ecofeminism offers a unique perspective on the connections between these issues and how we relate to the natural world. Within this framework, multiple levels of existence intersect, leading to a more profound interconnection of matters that influence our social and environmental welfare.

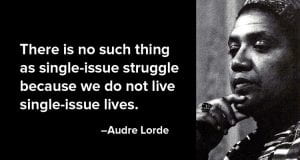

At the heart of ecofeminist thought lies the recognition that environmental degradation and social inequality are not individual concerns but rather indications of a more extensive systemic issue. The concept of intersectionality is fundamental to this ideology as it highlights the significance of recognizing the numerous ways in which women may encounter oppression when various forms of oppression intersect and influence both people and the natural world.

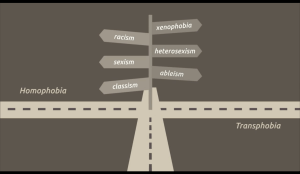

Intersectionality, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, refers to the interlocking nature of various forms of oppression and marginalization experienced by individuals who belong to multiple minority groups. Through this lens, the ecofeminist perspective aims to challenge the traditional notion of nature as a mere resource and commodity to be exploited as it advocates for a more comprehensive method of recognizing the inherent worth of all living beings. This approach helps to highlight the various aspects of race, class, gender, disability, sexuality, caste, religion, and age, and their diverse and unique impacts on discrimination, oppression, and the identity of women and the natural environment (Kings, 64). This method can be best understood as a “web of entanglement” where each web spoke represents a continuous sequence of the various social categorizations mentioned here (Kings, 65). This “web” concept is central to this philosophy, describing the intricate and interconnected relationships between all living beings on the planet.

Understanding the historical implications of intersectionality in relation to the ecofeminist perspective is crucial. According to Hobgood-Oster’s Western view of ecofeminism, it is necessary to examine the oppression of both the natural world and women under patriarchal power structures together. In her essay, Ecofeminism: Historic and International Evolution, Hobgood-Oster acknowledges that patriarchal power structures, which have historically marginalized women, also contribute to the exploitation of the environment (2005).

Bina Agarwal’s 1992 article, “The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India”, further highlights the importance of acknowledging the unique relationships that women and men have with the natural world, which are shaped by their specific circumstances and ways of interacting with the environment. Agarwal argues that knowledge about the natural world is largely experiential, and as such, is shaped by the same social structures that shape people’s interactions with nature (126).

However, Leah Thomas takes the issue even further in her article “The Difference Between Ecofeminism & Intersectional Environmentalism”, as she highlights the importance of comprehending the historical implications of intersectionality when considering the ecofeminist viewpoint. Although she agrees that ecofeminism emphasizes the interconnectedness of the exploitation of women and the natural world under patriarchal power structures, she also recognizes that this approach may overlook the disproportionate impacts of environmental degradation on marginalized communities (2020).

Thomas reminds us that while the ecofeminist perspective primarily focuses on the connection between the oppression of women and the exploitation of the natural world, it does not consider the ways in which environmental degradation affects people of different identities, including people of color, indigenous people, LGBTQ+ individuals, low-income individuals, and others (2020). She argues that in contrast, intersectional environmentalism expands upon the ecofeminist perspective by considering the intersection of various aspects of an individual’s identity in relation to environmental issues and seeks to address the interconnectedness of environmental and social justice concerns.

The concept of intersectional environmentalism recognizes the interconnectedness between various forms of oppression and the environment. In this context, a garden serves as a powerful metaphor for understanding the delicate balance of the natural world and the interdependence of all living things. Intersectional environmentalism recognizes that humans are not separate from nature but an integral part of it, and our actions have an impact on the health and wellbeing of the entire ecosystem. Plants, animals, and insects all play crucial roles in a garden’s ecosystem, highlighting the interconnectedness and fragility of nature.

Tending to a garden is not just about nurturing the plants and animals within it but also nurturing our connection to the natural world. Intersectional environmentalism emphasizes the significance of diversity in a garden as a symbol of strength as each plant and animal plays a unique role working collaboratively to promote growth and health in support of protecting and preserving the biodiversity, essential for the long-term survival of all life on earth. Ultimately, a garden is not just a physical location but also a spiritual and emotional space for reflection and contemplation where one can connect with the natural world, appreciate its beauty and complexity, and reflect on our relationship with the environment.

While ecofeminism and intersectional environmentalism both recognize the link between environmental degradation and societal problems, intersectional environmentalism expands upon the ecofeminist perspective by addressing environmental issues in a more inclusive and equitable manner and considering the intersection of various aspects of an individual’s identity to recognize the disproportionate impacts of environmental degradation on marginalized communities.

Works Cited:

Agarwal, Bina. “The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India.” Feminist Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 1992, pp. 119–158., https://doi.org/10.2307/3178217.

Hobgood-Oster, Laura. “Ecofeminism: Historic and International Evolution.” Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, edited by Bron Taylor, Continuum, London & New York , 2005, pp. 533–539, http://www.religionandnature.com/ern/sample/Hobgood-Oster–Ecofeminism.pdf.

Kings, A.E. “Intersectionality and the Changing Face of Ecofeminism.” Ethics and the Environment, vol. 22, no. 1, 2017, pp. 63–87., https://doi.org/10.2979/ethicsenviro.22.1.04.

Thomas, Leah. “The Difference between Ecofeminism & Intersectional Environmentalism.” The Good Trade, 11 Aug. 2020, https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/ecofeminism-intersectional-environmentalism-difference/.

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products

with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy

apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with

Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping

with Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products with

bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with

Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products

with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products

with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://anonymousgunshop.com/ Buy Gun Anonymously Online

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://anonymousgunshop.com/ Buy Gun Anonymously Online

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products

with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.net Apple bitcoins |

buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://cryptobitmart.comCryptobitmart | Online Shopping with Cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and

cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.com Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applecryptos.com Apple4 bitcoin | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.net Apple bitcoins | buy

apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.co Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency

https://applebitcoins.co Apple bitcoins | buy apple products with bitcoin and cryptocurrency