An Image is Worth a Thousand Words…or more!

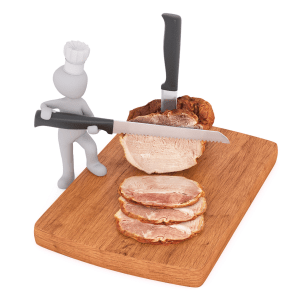

The image above may seem to depict a meaningless relationship between humans and food; perhaps an advertisement for a pork food-processing company. However, when observed from a vegetarian ecofeminist perspective, it can be interpreted as several representations of the problematic and unsustainable relationship between humans and nature, as well as the perpetuation of gendered patriarchal norms.

For instance, the scene of the stick figure chef (assumed to be male), with one foot on the cutting board, portrays a sense of human domination over animals, and the use of a meat fork to hold the pork roast in place while it is being sliced, reinforces the notion. The depiction simultaneously reflects a patriarchal society that values meat consumption as a sign of masculinity and power which perpetuates the idea that men should consume meat to maintain their social status and strength, as well as portrays the interconnectedness between the oppression of women and non-human animals, that is a central tenet of ecofeminism.

Moreover, the image highlights the patriarchal structure of the food industry, where men dominate the profession of cooking and butchery. Therefore, the image also reinforces the idea that the food industry is not only exploitative of animals and nature, but also emphasizes gender binary and gender inequality. Further, the use of a gender-neutral figure in the image underscores that speciesism is a problem that goes beyond social categories like gender and race.

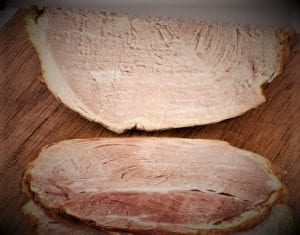

Furthermore, the carvings on the pork roast resembles tree rings and is a visual metaphor that draws attention to the interconnectedness of nature and the animals that inhabit it. The image portrays speciesism and the “unequal distributions” of power and the exploitation of “nonhuman animals, their reproduction and their bodies” for human consumption (Gaard, 20), as the stick figure chef is shown as the one with power, taking the life of an animal to satisfy human taste preferences without concern for their welfare or inherent worth. This can be further observed by the representation of the pork roast as a tree, and its carving marks implying that the animal had a life, and its death has a story to tell, just as the rings of a tree represent its life history. It challenges the notion of animals being mere commodities that exist solely for human use and consumption by acknowledging the value and worth of their lives.

Considering the examples provided here, it is easy to see how gendered food practices related to food that are influenced by gender norms and expectations, reinforce patriarchal norms and perpetuate speciesism. These practices can involve food preparation, consumption, and distribution, and can vary across cultures and contexts. Vegetarian ecofeminism seeks to address these issues by recognizing the interrelation of gender, ecology, and food systems, and challenging the oppressive and unsustainable practices that have become normalized in our culture.

One example of a normalized gendered food practice is the association of meat consumption with masculinity, which as previously mentioned, is reinforced by the depiction of the stick figure chef using a meat fork to hold the pork roast in place while it is being sliced. This image reinforces the idea that meat consumption is a sign of strength and power, which perpetuates the social construct of gender and reinforces harmful stereotypes about men and women’s food choices: “The man orders the steak. The woman, a salad” (Meat Heads, 2017). Vegetarian ecofeminism calls for the rejection of this ideology and promotes a more inclusive and diverse range of dietary options.

Another normalized example of a gendered food practice is the pressure placed on women to conform to beauty standards by adopting specific diets or avoiding certain foods. Therefore, “because women, more then men, experience the effects of culturally sanctioned oppressive attitudes toward the appropriate shape of the body” (Curtin, 1), women may feel the need to achieve a certain body shape or size in order to be considered attractive or feminine. This can lead to the adoption of restrictive diets or the avoidance of certain foods, which can have harmful consequences for physical and emotional health, such as anorexia nervosa, which Susan Bordo argues “is a ‘psychopathology’ made possible by Cartesian* attitudes toward the body at a popular level” (Bordo as cited in Curtin 1991).

Another gendered food practice involving women is the expectation for women to prepare and serve food for others. This expectation is often reinforced in households, restaurants, and social events, where women are expected to take on the role of food preparers and servers. This can contribute to reinforcing gender stereotypes and undervaluing women’s work, as food preparation and service is often seen as women’s work.

Furthermore, these gendered food practices can lead to an unequal distribution of labor in households, where women may bear the brunt of food-related responsibilities in addition to other tasks like childcare and household maintenance. This can create added pressure and stress for women and have a range of impacts on physical and emotional health that contribute to feelings of burnout and overwhelm.

It is important to recognize and challenge these practices in order to promote more equitable and healthy relationships with food. Vegetarian ecofeminism recognizes the interconnectedness of gender and ecology and seeks to challenge the oppressive practices that have become normalized in our culture.

Ecofeminists perceive non-human animals as beings that are equal in moral value to humans, with their own intrinsic worth and rights. They reject the notion that humans are superior to other animals and argue that the exploitation and domination of non-human animals is linked to the oppression of women and other marginalized groups.

Greta Gaard, in “Ecofeminism on the wing: Perspectives on human-animal relations,” argues that non-human animals should be recognized as individuals with their own interests and desires, rather than simply as resources to be used by humans. And while we “don’t have good choices that allow us to live in this culture and maintain our relationship with other animals without violating their integrity” (22), she calls for a shift away from a human-centered worldview towards an ecological worldview that recognizes the interdependence of all living beings and the importance of preserving biodiversity.

Deane Curtin, in “Contextual Moral Vegetarianism,” argues that our relationship to non-human animals should be based on a recognition of their inherent value and a commitment to treating them with respect and care. She suggests that a contextual approach to moral vegetarianism, in which individuals make choices about their diets based on the specific conditions of the animals involved and the environmental impact of their food choices, can help to promote greater ethical awareness and responsibility. She reminds us that “To choose one’s diet in a patriarchal culture is one way of politicizing an ethic of care” (3). That is, the act of choosing one’s diet is not merely a personal decision but is also a political act with ethical implications, and that in a patriarchal culture, where women and other marginalized groups are often subject to exploitation and oppression, choosing to adopt an ethic of care in relation to one’s diet can be a way of resisting these pressures and promoting more compassionate and respectful relationships.

Both Gaard and Curtin emphasize the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of all living beings and the need to reject the notion that humans are separate from and superior to other animals. They call for a shift towards a more compassionate and respectful relationship with non-human animals, based on an understanding of their intrinsic value and the importance of preserving ecological diversity.

Overall, a vegetarian ecofeminist perspective emphasizes the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of all beings and promoting a more compassionate, just, and sustainable way of living. By challenging the oppressive and unsustainable practices that have become normalized in our culture, we can work towards creating a more equitable and sustainable way of living that recognizes the interconnectedness of all beings.

===

* Cartesian feminism refers to a philosophical and feminist movement that seeks to reconcile feminist values with the rationalist philosophy of René Descartes (Pellegrin, 2019). To read more about Cartesian Feminism, see link below.

Works Cited:

Curtin, Deane. “Toward an Ecological Ethic of Care.” Hypatia, vol. 6, no. 1, 1991, pp. 60–74., https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1991.tb00209.x. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.

Eisenberg, Zoe. “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity.” HuffPost, 13 Jan. 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/meat-heads-new-study-focuses_b_8964048.

Gaard, Greta. “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations.” Women & Environments, 2001, https://www.academia.edu/2489929/Ecofeminism_on_the_Wing_Perspectives_on_Human_Animal_Relations. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.

Pellegrin, Marie-Fréderique, ‘Cartesianism and Feminism’, in Steven Nadler, Tad M. Schmaltz, and Delphine Antoine-Mahut (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Descartes and Cartesianism, Oxford Handbooks (2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 9 May 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198796909.013.35, accessed 23 Feb. 2023.

Rose – What an excellent post! I especially like the way in which you took the larger image and then broke it down into smaller sections, zooming in, and speaking to what each one might represent in relationship to ecofeminism vegetarianism. Your interpretation has many levels and encourages the reader to think beyond what is shown on the surface. To this extent, you weave the interconnectedness that we learned about in this week’s lesson, full circle.

As for gendered food practices, in my blog, I also touched upon the way in which women are expected to prepare, serve, and cleanup after others. I can vividly picture my grandma running around while everyone else ate. She always put the needs of others at her table first, which meant she rarely sat to enjoy a meal or serve herself a fair-sized portion. Like you speak to, this creates and imbalance in the gendered workload around eating, which typically falls to women.

Gaard uses her story about a bird to illustrate how all animals, human and non-human, are connected, and points out that we need only look to the dinner table to see how imbalanced this equation has become. “It’s hard to say whether the the most common site for human-animal relations occurs at the dinner table, where humans consume other animals (but not other humans), or below the dinner table where humans feed one oppressed animal species to another” (Gaard, 2014, Page 21). Not only have we asserted our righteousness over non-human animals, we then pass that on to pets as we decide what, when, and how they should eat. I think this presents an interesting aspect, and plays into the way in which the patriarchal power has intruded on all aspects of life. With this, the principles of ecofeminism vegetarianism can help us see the error of our ways in how we have become so disconnected to each other, and the world around us.

Gaard, G. (2014, May 22). Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations. https://www.academia.edu/2489929/Ecofeminism_on_the_Wing_Perspectives_on_Human_Animal_Relations

Hi Christine,

Unfortunately, in many cultures, mine included, women are still expected to take on the role of food preparers and servers while men enjoy their meal. Your personal story about your grandmother took me back to a time in my childhood when my own grandmother did the same. To a certain extent I do this as well but not for the same reasons. I am usually the last one at the table to ensure others have what they need before I sit down which often results in them being halfway done with their meals when I am taking the first bite. This is definitely a learned behavior at the intersection of gender and cultural norms, and does create an imbalance in the gendered workload around eating, that could lead to feelings of resentment and inequality. Ours are good examples of how these gendered expectations play out in real life.

Hi Rose,

I found your analysis of the included picture to be so enlightening! You made so many more connections that I didn’t even notice upon my first (or even second) pass. I thought that your decision to zoom in on the figure’s foot, which is stepping onto the cutting board, emphasized the idea of domination that the picture conveys.

And you’re so right; women and animals are oppressed in similar means under our patriarchal society. I came across this article by Angelica Florio titled “The Sexualization of Meat” and her ecofeminst conversation echoes your own. In that article she writes,

“In a patriarchal society, both animals and women are perceived as weaker than and inferior to men, and are objectified as a result. While humans (both men and women) objectify animals by killing them and turning them into fragmented pieces of “meat,” women are figuratively objectified and fragmented in patriarchal societies as well.”

She seemed to have this revelation when she was out to eat at a meat-centric restaurant with her family, and the waitress was describing the meal in terms of “beast” and locations like “upper thigh” or “back.” How can people speak about animals in such a similar way to our own human bodies and not see the connection, the similarities between us as two beings?

And it goes a step further with the exploration of animals and the unnecessary and degrading sexualization of women. Florio proposes the point,

“The construction of women as the weaker members in a patriarchal society has led to an association between women and animals. The focus on women’s bodies and the fragmenting of individual body parts causes women to become sexual objects, just as animals become objects when eaten as “meat.” When a man identifies himself as a “breast man,” “leg man” or “ass man” he reduces women to their body parts, consumed like meat. ”

Even with all the ecofeminst theory we’ve been consuming in the past few weeks, this wasn’t a connection that I had made on my own (like with your analysis of the attached photo). But once the idea entered my mind, it made an integral shift in my worldview, and especially my ecofeminist view.

If you want to check out the entire article, here’s the link:

http://www.ciphermagazine.com/articles/2017/2/19/the-sexualization-of-meat

Hi Jasmine,

Thank you for sharing your thoughts on the connection between the oppression of women and animals in our patriarchal society. I’m glad that my analysis of the picture resonated with you and that you found Angelica Florio’s article on the sexualization of meat thought-provoking.

The parallels between the objectification of women and animals are indeed striking, and I feel this class has definitely made me hyperaware of it. Women and non-human animals are both seen as weaker and inferior to men and are treated as objects to be consumed or dominated. In the case of animals, they are killed and turned into pieces of meat, while women are often reduced to their body parts and objectified as sexual objects.

Florio’s point about the association between women and animals in patriarchal societies is particularly relevant here. The focus on women’s bodies and the fragmentation of individual body parts not only reinforces patriarchal power structures but also objectifies women in a way that is similar to the objectification of animals.

The fact that people can speak about animals in such similar terms to human bodies, without recognizing the connection between the two, is a testament to the deeply ingrained nature of patriarchy in our culture. It’s only by recognizing and addressing these connections that we can hope to break down the systems of oppression that harm both women and non-human animals.

I’m happy to hear that your worldview has shifted as a result of this new perspective. It’s important to continue exploring and learning about these issues, as it can help us to better understand the world around us and work towards creating a more just and equitable society for all. I know this class has certainly been an eye opener for me.

Thanks again for sharing your thoughts and the link to the article. I look forward to reading more about these important topics.

Hi Kylie,

Upon first viewing the image, I was drawn to the stick figure’s foot on the cutting board. Two thoughts immediately came to mind. The first being the familiar gesture of stomping the foot as a signal for a dog to comply with a command. This was a common practice during my upbringing in Brazil. The second thought stemmed from my father’s habit of using the same gesture as a sign that my siblings and I had pushed him to his limit, which fortunately for us, did not happen often. In contrast, my mother’s signal was more subdued, yet carried significant weight – the calling of our full names. Naturally, I found the image to highlight the control that humans have over non-human animals in the food industry.

Your reference to Gaard’s work on the intersection of masculinity and the oppression of non-human animals was particularly enlightening. It is clear that societal expectations around gender roles and emotions can contribute to the perpetuation of systemic oppression in various forms, including the exploitation of non-human animals for profit. Sadly, the societal construction of masculinity as aggressive and dominant has been ingrained in men from a young age and reinforced by media and cultural norms. This leads to a suppression of emotions such as sympathy and humility, which are seen as “feminine” and therefore weak. We don’t often thing of this, but men can become disenfranchised by gender norms. I have read some interesting articles on this subject and will link to one at the end.

I appreciate your thoughtful insights and your reference to Greta Gaard’s work on the subject. I also appreciate your recognition of the gendered practices in food preparation that can contribute to the marginalization of certain groups. It is essential to recognize and address the various forms of oppression that exist in our society, including heterosexism, racism, and classism, as Gaard notes.

Thank you for your thoughtful response and for sharing your insightgs; I always look forward to your observations. I will definitely refer to Gaard’s work to further my understanding of the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective.

If you would like to read more on the ways men may feel disenfranchised by gender norms, see link below.

https://hbr.org/2018/10/how-men-get-penalized-for-straying-from-masculine-norms

Hi Rose,

This was a beautifully written blog post that effectively discussed the significance of the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective. I enjoyed reading your breakdown of each detail included in the image provided for interpretation. Your analysis of the figure’s foot placed on the cutting board as if having control over the meat being sliced was a very interesting detail to point out. I can absolutely see the correlation there with further emphasis of exploitation with the use of two knives rather than one to demonstrate the excess violence committed against the non-human animal, even after being killed for consumption in the first place. The disconnect between human and non-human animals has grown with the expansion of industrialization and capitalism, particularly with the emergence of factory farming. Androcentric culture has held the masculine perspective in the center of society. With the exploitation of non-human animals comes profit to those at the authority level of these major corporations, most often held by powerful white men. Greta Gaard offers an insight on the environmental ethics of this in her piece, “Vegetarian Ecofeminism: A Review Essay” in which she writes, “But the ability to sympathize, like all emotions, is influenced by our social and political contexts…because Western culture has defined ongoing suffering as ‘unmanly,’ many men learn to repress or deny their own suffering and are unable to sympathize with others’ suffering” (Gaard 120). As vegetarian ecofeminism calls for the need to sympathize and have compassion for the lives of non-human animals, Gaard’s analysis provides us that the oppression of non-human animals is linked to the construct of masculinity in a patriarchal society. Men are taught that they are not to have the emotions of sympathy and humility but instead anger and dominance. Anything outside the confines of “masculine” is considered deviant. This embeds itself into the food industry through marketing and gender stereotyping as men are praised for consuming meat while women are confined to smaller “clean” eating practices to maintain the “ideal thinness” of the body. In connection to Gaard’s work, because men are told to mask any emotions of sympathy, the connection between human and non-human animals is diminished. There is no compassion for suffering both on the CEO level and civilian level as profit and control are instilled in societal values. This is where the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective is significant in recognizing that we need not only to focus on the oppression of nature and women, but of non-human animals as well. As you mentioned, there are also gendered practices in food preparation where the women are expected to cook and serve food for others. Many cultures expect women to eat last, their husbands and children first. I bring this up as heteronormative expectations are also to be analyzed through a vegetarian ecofeminist perspective as Gaard states, “…it is imperative that ecofeminists address the problem of heterosexism, racism, and classism, both within our movements and within the larger culture…some vegetarian ecofeminists have been inspired to address speciesism from their own oppression as lesbians and bisexual women and have begun to make connections between the animalization of homosexuals and people of color…” (Gaard 140). This allows us to expand our thinking beyond essentialism and acknowledge that all experiences are unique, and the exploitation of non-human animals is connected to that of those that are disadvantaged under patriarchy. It is not until we recognize our responsibility in caring for all life, not just our own, that we will end the multidimensional layers of oppression.

If you are interested in reading the additional source by Greta Gaard, the citation information is as follows:

Gaard, Greta. “Vegetarian Ecofeminism: A Review Essay.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 23, no. 3, 2002, pp. 117–146., https://www.jstor.org/stable/3347337?seq=24. Accessed 25 Feb. 2023.

Best,

Kylie Coutinho