An Image is Worth a Thousand Words…or more!

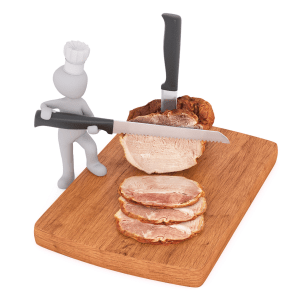

The image above may seem to depict a meaningless relationship between humans and food; perhaps an advertisement for a pork food-processing company. However, when observed from a vegetarian ecofeminist perspective, it can be interpreted as several representations of the problematic and unsustainable relationship between humans and nature, as well as the perpetuation of gendered patriarchal norms.

For instance, the scene of the stick figure chef (assumed to be male), with one foot on the cutting board, portrays a sense of human domination over animals, and the use of a meat fork to hold the pork roast in place while it is being sliced, reinforces the notion. The depiction simultaneously reflects a patriarchal society that values meat consumption as a sign of masculinity and power which perpetuates the idea that men should consume meat to maintain their social status and strength, as well as portrays the interconnectedness between the oppression of women and non-human animals, that is a central tenet of ecofeminism.

Moreover, the image highlights the patriarchal structure of the food industry, where men dominate the profession of cooking and butchery. Therefore, the image also reinforces the idea that the food industry is not only exploitative of animals and nature, but also emphasizes gender binary and gender inequality. Further, the use of a gender-neutral figure in the image underscores that speciesism is a problem that goes beyond social categories like gender and race.

Furthermore, the carvings on the pork roast resembles tree rings and is a visual metaphor that draws attention to the interconnectedness of nature and the animals that inhabit it. The image portrays speciesism and the “unequal distributions” of power and the exploitation of “nonhuman animals, their reproduction and their bodies” for human consumption (Gaard, 20), as the stick figure chef is shown as the one with power, taking the life of an animal to satisfy human taste preferences without concern for their welfare or inherent worth. This can be further observed by the representation of the pork roast as a tree, and its carving marks implying that the animal had a life, and its death has a story to tell, just as the rings of a tree represent its life history. It challenges the notion of animals being mere commodities that exist solely for human use and consumption by acknowledging the value and worth of their lives.

Considering the examples provided here, it is easy to see how gendered food practices related to food that are influenced by gender norms and expectations, reinforce patriarchal norms and perpetuate speciesism. These practices can involve food preparation, consumption, and distribution, and can vary across cultures and contexts. Vegetarian ecofeminism seeks to address these issues by recognizing the interrelation of gender, ecology, and food systems, and challenging the oppressive and unsustainable practices that have become normalized in our culture.

One example of a normalized gendered food practice is the association of meat consumption with masculinity, which as previously mentioned, is reinforced by the depiction of the stick figure chef using a meat fork to hold the pork roast in place while it is being sliced. This image reinforces the idea that meat consumption is a sign of strength and power, which perpetuates the social construct of gender and reinforces harmful stereotypes about men and women’s food choices: “The man orders the steak. The woman, a salad” (Meat Heads, 2017). Vegetarian ecofeminism calls for the rejection of this ideology and promotes a more inclusive and diverse range of dietary options.

Another normalized example of a gendered food practice is the pressure placed on women to conform to beauty standards by adopting specific diets or avoiding certain foods. Therefore, “because women, more then men, experience the effects of culturally sanctioned oppressive attitudes toward the appropriate shape of the body” (Curtin, 1), women may feel the need to achieve a certain body shape or size in order to be considered attractive or feminine. This can lead to the adoption of restrictive diets or the avoidance of certain foods, which can have harmful consequences for physical and emotional health, such as anorexia nervosa, which Susan Bordo argues “is a ‘psychopathology’ made possible by Cartesian* attitudes toward the body at a popular level” (Bordo as cited in Curtin 1991).

Another gendered food practice involving women is the expectation for women to prepare and serve food for others. This expectation is often reinforced in households, restaurants, and social events, where women are expected to take on the role of food preparers and servers. This can contribute to reinforcing gender stereotypes and undervaluing women’s work, as food preparation and service is often seen as women’s work.

Furthermore, these gendered food practices can lead to an unequal distribution of labor in households, where women may bear the brunt of food-related responsibilities in addition to other tasks like childcare and household maintenance. This can create added pressure and stress for women and have a range of impacts on physical and emotional health that contribute to feelings of burnout and overwhelm.

It is important to recognize and challenge these practices in order to promote more equitable and healthy relationships with food. Vegetarian ecofeminism recognizes the interconnectedness of gender and ecology and seeks to challenge the oppressive practices that have become normalized in our culture.

Ecofeminists perceive non-human animals as beings that are equal in moral value to humans, with their own intrinsic worth and rights. They reject the notion that humans are superior to other animals and argue that the exploitation and domination of non-human animals is linked to the oppression of women and other marginalized groups.

Greta Gaard, in “Ecofeminism on the wing: Perspectives on human-animal relations,” argues that non-human animals should be recognized as individuals with their own interests and desires, rather than simply as resources to be used by humans. And while we “don’t have good choices that allow us to live in this culture and maintain our relationship with other animals without violating their integrity” (22), she calls for a shift away from a human-centered worldview towards an ecological worldview that recognizes the interdependence of all living beings and the importance of preserving biodiversity.

Deane Curtin, in “Contextual Moral Vegetarianism,” argues that our relationship to non-human animals should be based on a recognition of their inherent value and a commitment to treating them with respect and care. She suggests that a contextual approach to moral vegetarianism, in which individuals make choices about their diets based on the specific conditions of the animals involved and the environmental impact of their food choices, can help to promote greater ethical awareness and responsibility. She reminds us that “To choose one’s diet in a patriarchal culture is one way of politicizing an ethic of care” (3). That is, the act of choosing one’s diet is not merely a personal decision but is also a political act with ethical implications, and that in a patriarchal culture, where women and other marginalized groups are often subject to exploitation and oppression, choosing to adopt an ethic of care in relation to one’s diet can be a way of resisting these pressures and promoting more compassionate and respectful relationships.

Both Gaard and Curtin emphasize the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of all living beings and the need to reject the notion that humans are separate from and superior to other animals. They call for a shift towards a more compassionate and respectful relationship with non-human animals, based on an understanding of their intrinsic value and the importance of preserving ecological diversity.

Overall, a vegetarian ecofeminist perspective emphasizes the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of all beings and promoting a more compassionate, just, and sustainable way of living. By challenging the oppressive and unsustainable practices that have become normalized in our culture, we can work towards creating a more equitable and sustainable way of living that recognizes the interconnectedness of all beings.

===

* Cartesian feminism refers to a philosophical and feminist movement that seeks to reconcile feminist values with the rationalist philosophy of René Descartes (Pellegrin, 2019). To read more about Cartesian Feminism, see link below.

Works Cited:

Curtin, Deane. “Toward an Ecological Ethic of Care.” Hypatia, vol. 6, no. 1, 1991, pp. 60–74., https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1991.tb00209.x. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.

Eisenberg, Zoe. “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity.” HuffPost, 13 Jan. 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/meat-heads-new-study-focuses_b_8964048.

Gaard, Greta. “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations.” Women & Environments, 2001, https://www.academia.edu/2489929/Ecofeminism_on_the_Wing_Perspectives_on_Human_Animal_Relations. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.

Pellegrin, Marie-Fréderique, ‘Cartesianism and Feminism’, in Steven Nadler, Tad M. Schmaltz, and Delphine Antoine-Mahut (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Descartes and Cartesianism, Oxford Handbooks (2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 9 May 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198796909.013.35, accessed 23 Feb. 2023.